Home » Journal Articles » Thoughts & Opinions » Sculptural Portrait

During the last five years, I have been creating my favorite type of sculpture–round and relief sculptural portraits. There were portraits of living people (Dr. Denton Rossell, Dr. Eugene Natkin, Cindy Growford, Elaina Mason) and people who lived in the past (attorney George Powell, Abraham J. Heschel, Sigmund Freud, Aristotle, Thomas Jefferson, Princess Diana), and imaginary persons (Ally, Millina). Each of these portraits needed a different approach. Some of them were done in life size, and some in smaller scale. Each portrait had a different composition and modeling, but all of them required something mutual: the portrait should be an objective and truthful representation of the person.

The main indication of the portrait is its likeness with the model. But more is needed for a portrait to be considered a truthful representation of the person. “An ability to copy portraits from the model is a talent to some degree, but it is not all,” according to Russian writer Vissarion Belinsky. A real portrait, he continued, “is a piece of art, that captures not only the likeness, but also the soul of the model.” To reach this level, the artist searches for the “synthetic moment” in which not only specific facial features of the person have been depicted, but all his life, his biography, all his present, past and even future life. All that is part of the subject’s real likeness.

A live model gives the artist soul, and from the soul comes its greatest beauty unlimited information. “The human body is, above all, the mirror of the soul, and from the soul comes its greatest beauty,” August Rodin said. And famous artist Renato Gutuzo thought that, when we are talking about a possible correlation between the physical appearance and psychological aspect of the model, for the artist who can see it, it is almost the same.

To show the person in the way an artist understands it, the artist goes through a screening process to select information about the model and the specific facial features for expression. The artist exaggerates some of them and ignores all that are unimportant according to his philosophy, temperment and style. From the selection of the model through all the sculpting processes up to finishing and installation-through all the steps of the decision making–the sculptor shows his outlook, philosophy and circle of his interests. That is why two portraits of the same person done by two artists are not alike, and why, very often, we can say that the artist expresses himself in this portrait.

A sculptural portrait, differing from other types of art, is a three-dimensional image of the model. The use of color, value, and contrasts are not available to the sculptor as they are to a painter. A painting is a two-dimensional object. A third dimension is an illusion and the artist represents it by using principles of linear color and tone perspective. In a sculptural portrait, the third dimension is real and plays the same role as the other two dimensions.

In the performing arts and literature (“timing arts”), the author can portray man’s spirit using a broad arsenal of tools to describe the hero. It can be a verbal description of his life, behavior, and way of thinking. The author can also use the hero’s words or another person’s words to characterize a hero and can say almost nothing about his appearance.

In visual arts, the artist is able to capture the character of the soul of the model through representation of the model’s plastically expressive image only.

On the other hand, a viewer has an opportunity to observe the sculptural portrait from all sides and many points of view. It provides an opportunity show many specific details. The composition of the portrait and the form’s continuous movement lead a viewer from one vlewpoint to another around a portrait. It helps the artist to show a model “in time” and almost equal to “timing arts” by effect.

A sculptural portrait is a monochrome object in most cases. The form of the sculpture can be seen due to lighting. All objects in nature are divided from one another by color and chiaroscuro–treatment of light and shade. We can see the form of the sculpture only because of light and shade on its surface. A salient part of the sculpture reflects the light and a cave creates the shadow. The form of the monochrome sculptural portrait can be made only by applying specific modeling methods to the sculptural surface, creating a contrast between light and shadow. The sculptor shows the darkness of the shadow area by modulating the deepness of the undercuts. The deeper an undercut, the darker it seems to be for the observer. Lighter halftones can be done in the same way. This combination in harmony creates the sculptural forms. Since sculptural forms are visible only because of contrast between darker and lighter areas, similar t( monochrome drawing, the sculpture can be called “three-dimensional drawing.”

This concept is most obvious in the low-relief portrait. The relief is a sculpture that is designed to be attached to any surface. A low-relief portrait is also a three-dimensional sculpture with the third dimension of approximately 0.25 inches. Similar to drawing, it consists of lines, linear perspective, and the sculptural shapes of the face.

The composition of relief portraits can include a portrait itself, pictorial background, and text. Its scale, shape, and texture, along with the modeling method, can tel1 a story about the sitter, the model’s occupation, individual interests’ time, surroundings, etc.

When I am working on the portrait of a living person, I am trying to show my impression of this model collected during personal contact with the sitter. The work on the portrait of a person who lived in the past (historical portrait) starts in the library. I am searching for equivalent information about a model from publications, from living members of the family, studying available memoirs, etc.

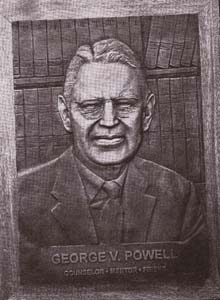

The portrait of attorney George V Powell is a sample of an historical portrait. He was a co-owner of Lane, Powel1, Spears, Lubersky, a law firm in

After talking to Mr. Powel1’s co-workers and his daughter, reading material about him from the firm’s officials, and studying the family photos, I formed my opinion about him. I spent almost two weeks working on the composition and selecting the hackground, text, and relative sizes of aU components. As soon as major decisions were made, I1 started to sculpt his portrait in clay.

My idea was to show George Powell as a mentor and friend, wise and intelligent professional, and caring husband, father, and grandfather. I chose his library for the background and showed George wearing glasses. When I was done with the clay model, I sent photos of it to Jane Ashe, Marketing Director of the firm. She set up a preview of my work with Powel1′ s family members. This meeting was successful. Jane ordered, not one, but two bronze copies.

The foundry that I had worked with for several years was ready to make the rubber molds for the portrait itself and for the text. Very soon 1 got the molds and first wax copies. A couple of days were spent to work on waxes and combine the portrait and text together. Everything was ready to make the bronze. I never expected problems in this state of the job, but there were. First the fireproof ceramic mold for the bronze got cracked and the bronze ran out of the mold. I made other waxes, but it happened again and again.

Jane had already scheduled a company meeting in honor of George Powel1. The firm planned to dedicate the Board Room in the

I couldn’t take a risk a fourth time and 1 shifted the work to Bob Mortinson’s foundry. He was very cooperative and reorganized his busy schedule to do this emergency work. In five days, he made a casting. I placed the second casting in Todd Petrel1e’s foundry to have both of them ready by the day of the dedication. The second plaque was done one week before the company meeting. It gave me time for ordering the frames (many thanks to Steve Sandry for the wonderful frames out of

The sculpture was final1y mounted in the conference room one day before the dedication. The celebration of Mr. George Powel1 occurred as scheduled and included members of Mr. Powell’s family, Counsel of Washington, in addition to Lane, Powell, Spears, and Lubersky’s attorneys and staff. The second casting was given to the Powel1 family.

I hope that I reached my goal. I believe I did according to Jane Ashe’s letter. She wrote: “Thank you again for such beautiful plaques, both reflecting the true spirit of our friend, George Powell.”

We need some kind of descriptive text here.