Home » Journal Articles » Thoughts & Opinions » Sculptors We Hardly Ever Hear About: François Pompon

One October afternoon, a few years ago, I sat cross-legged in a circle with about twenty 4th grade school children, on the main floor of the Musée d’Orsayin Paris. In the center of the circle was a larger than life, (2 metres 50 cm. long – nearly 10 feet) sculpture of a white marble polar bear. The children all had sketch-pads and were dutifully rendering what they saw before them. I, who just happened to join the group by chance, simply sat and stared. What was it, I asked myself, that made this sculpture so compelling? What was so sophisticated about it that it sat in a place of honor in one of the premier museums of the world? What was so simple about it that teachers brought ten year-olds to see it and draw it? The sculpture, “L’Ours Blanc,” a giant polar bear in rolling stride, is perhaps one of the best known sculptural works of the early 20th century. Surprisingly it is by one of the least well-known sculptors: Francois Pompon (1855-1933.)

At the 1922 Fall Salon in Paris, all the buzz was about the ‘bel ours polaire. ‘Who had carved it? Was it Rodin? Was it another famous sculptor of the time? Everyone was surprised when the name of the sculptor was announced. It was a name few had heard of even then, and a name that always brought a smile to people as they said it: Pompon.

Francois Pompon was already sixty-seven years old when he showed “The White Bear” at the Fall Salon. Although he had been carving for years, and had worked in the studio of Rodin and Camille Claudel, few people knew of him. Slight of stature and retiring by nature, he much preferred the company of the animals who were his models and friends. Particularly his pigeon Nicolas and his dog, Nenett.

Pompon came from a family of woodworkers, but he had always preferred stone. When he was fifteen he apprenticed with a marble cutter in Dijon, and at twenty, he left his family in Bourgogne and came to Paris. There he took lodgings at 3, rue Campagne-Premiere in Monparnasse, where he lived for the rest of his life. It was here, five years later, he met and married, Berthe, a dress-maker.

He began by carving tombstones, then moved on to portraiture. He was known in the trade as a capable and skilled carver and was in demand to work in the studios of other more well-known sculptors, finishing their work or helping with large commissions.

Between 1890 and 1895, he worked in the studio of Auguste Rodin and Camille Claudel. In 1893 when Rodin “forgot” to pay him, Pompon took Rodin to court. It’s a sign of Rodin’s respect for Pompon that he not only settled his debt but then made Pompon the head of his studio.

In 1896 Pompon went to the studio of Rene de Saint-Marceaux, another important sculptor of the time. He happily worked there for seventeen years. During that time, he found time to do some of his own work. Rather than the large commissions or portraiture that he had been familiar with, his work consisted of roosters, rabbits and farm animals.

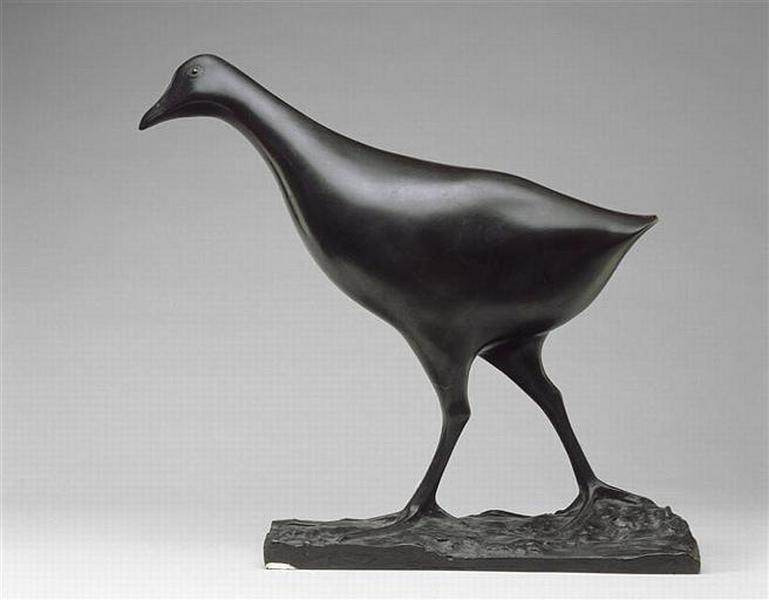

He spent many hours observing and sketching animals at the Jardin des Plantes (where there is a small zoo,) in Paris. He simplified and simplified until he perfected his iconic style. Little by little he eliminated details and saved “only what was indispensable.” He was known to say: “I love sculptures without holes or shadows.”

At the time, the simplicity of his sculpture struck critiques as odd. “How can you have a rooster without feathers, or an animal without fur?” He became known for making ‘trinkets,’ but no one took him seriously. In 1915, Rene de Saint-Marceaux died and Pompon lost his livelihood. It was hard going for Pompon. No one was interested in hiring a small old man. To make ends meet, Pompon worked at a large department store in Paris, la Samaritaine. Berthe died in 1921.

At this low point in his life, a young painter friend of his, Rene Demeurisse, visited Pompon and was enchanted by all the small plaster statues of animals lined up on shelves in his studio. Demeurissse invited his friends over to see them. One of them, the sculptor Antoine Bourdelle, suggested that Pompon work large.

The result: The Salon of 1922, fame and success. For the rest of his life, Pompon carved the sculptures that he liked the best. Many he did in stone and many he did in plaster which were later turned into bronze under his supervision.

People came from all over to visit his studio and his works were shown internationally. But celebrity didn’t change Pompon or his habits. “When you become famous,” he would advise, “close yourself up in your studio and work.”

And that’s what he did.

His work sold for huge sums, he was rich and he was famous. But, still living at the same modest address and working in his studio each day, Pompon continued to carve sculptures of birds and animals. His style, eschewed detail and emphasized soul and body, spirit and form. He became well-known as an ‘animaliere’ and his sleek style influenced other sculptors including Brancussi and Arp. His work constitutes a large step in the development of sculpture between Rodin and the modernists.

Francois Pompon died on the 6th of May in 1933. Services were held at the Cathedral de Notre-Dame in Paris, but he is buried in Saulieu, Bourgogne, his hometown, next to his family and Berthe, his wife and companion of twenty-nine years.

We need some kind of descriptive text here.