Every spring the melting snows off the Cascades bring down a delightful assortment of rounded and fractured stones and cobbles that only nature can prepare for the coming months of the rivers’ ongoing garage sale.

As the waters recede and expose the year’s offerings, my fellow stone carvers and I trek to our favorite rivers in the foothills to look for olivine, peridotite, serpentine, granite, jade, and whatever else may have washed down from the Cascades’ complex geology to inspire our sculptures.

There is much to be said for granite, peridotite, and jade, but one of my favorite stones to find in the rivers is olivine. It is tan on the outside, a variety of greens on the inside. When carved thinly and highly polished will become translucent.

It is more commonly known as dunite because, when fully oxidized, it has a orangish tan “dun” color. The dunite we find in the rivers has been tumbled on their journey downstream and you will only find tan rounded stones. The two+ mile wide by five mile long upper mantle uplift the Twin Sister formation to the west of Mount Baker, is one of the largest dunite deposits in North America and is where you can hike to find dunite which has been exposed since the glaciers receded 10,000 years ago.

When looking for stones I sometimes see a small cobble with an interesting shape, and it will speak to me that it’s a bowl or a platter, and the tan outside edge will become the rim of a bowl.

Other times I find a pleasing shaped stone that speaks to me and I feel a connection to, so I take it home, and wait to see/hear what it is eventually to become. I might see the head of a critter like a rabbit or am thinking of doing something for someone special going thru chemo and I find a frog.

Olivine is not a stone to be directly shaped with a hammer and chisel. It is a hard stone, 5-7 on the mohs scale, dense and heavy, with a variety of crystal sizes and a propensity to split along a hexagonal fracture pattern. It is a stone that works best with what we affectionately call spinning diamond tools. These are angle grinders, die grinders, dremels, and foredoms using diamond blades, burrs, and cup wheels to shape and form. Then using diamond pads and diamond paste the shine is brought out. These tools come from the granite countertop and lapidary worlds and do a very nice job sculpting olivine. I learned their use at the Northwest Stone Sculptors Association symposiums, one of the best places to meet other stone sculptors and learn to carve stone.

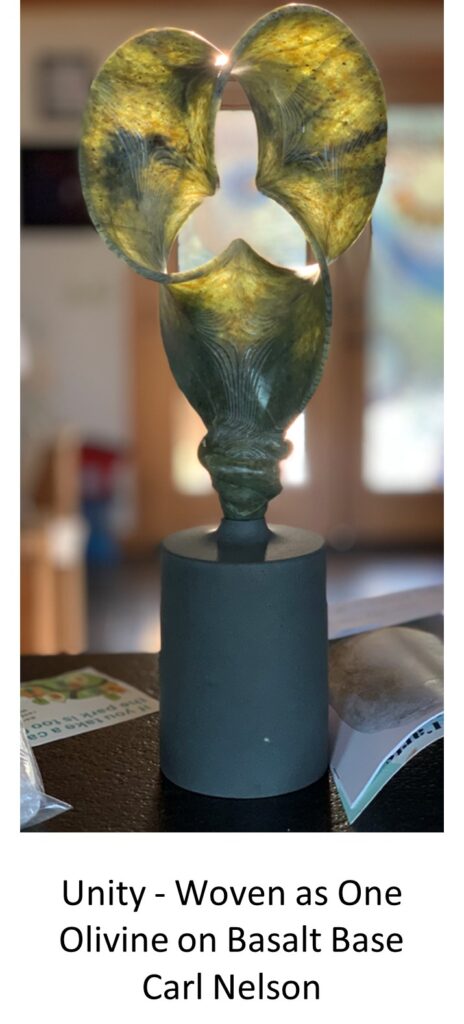

To be successful in creating a thin piece you will need a stone that has integrity that will hold together as you are working to thin it. One of the nice qualities about a river tumbled cobble is that to survive the bumping and tumbling it will have integrity. When I found the cobble with no cracks or fractures, which became Unity – Woven As One, I was pretty confident that I had the right stone.

For me the the most joyful discovery about olivine has been it’s translucency. If you have the patience to create an ⅛”or less thick surface the light will come through, revealing the matrix and small peridot crystals.

The other key to success for a thinned surface sculpture is to have a curving form and avoid long flat surfaces. I developed a möbius form for the Unity piece to represent the interweaving of the elements a community needs to provide its members to flourish – basic human needs, the foundations of well being, and opportunity.

Making the stone thin reveals the variation and nature of the specific piece of stone. Dunite from the quarry, or an outcropping, has much more variation and its nature has to be respected, carefully considered, and worked around.

The glacial deposits that were laid down as the glaciers melted are what underlie the abundance of rounded river rocks. The rivers are a convenient and ever changing place to find them, but there are other excellent places where people’s activities have revealed them. Road cuts, such as an old forest logging road can be a wonderful walk and place for discovery. Although not as glamorous, a visit to an old gravel pit or with permission a working one can be a treasure hunt with inspiring finds.

The forests of the Pacific Northwest help set the stage for the awe you can experience when foraging in the rivers for stones. The sound of the birds, the water in eddies and riffles as you walk along the banks, and the endless variations of size, color, and revealed geology especially when there’s a light mist and the rocks go from faint pastel grays to colorful reminders of their potential.

In Washington state the Northwest Stone Sculptors Association has a long standing relationship with an olivine quarry and has been able to arrange a guided trip once a year for its members to collect olivine and dunite from the quarry. One year while scrambling up a hillside, I found an interesting shaped hundred+ pound piece of dunite with an orange rind and a ⅜” wide band of peridot woven through it’s midsection. I could only guess what I would find inside and around the peridot. After help from fellow stone carvers getting it off the hillside and lugging it home, I was not disappointed. After many hours of grinding and meticulous work to thin it, the pattern revealed what looks like a kelp forest of dark and light greens beneath the orange rind.

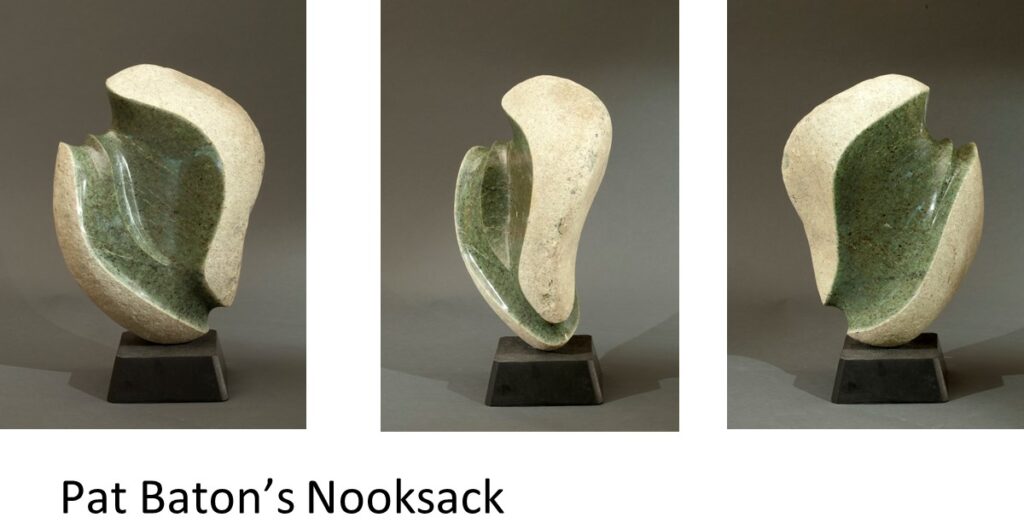

In this environment, it is easy to have a rock catch your eye and you feel pulled towards it. On one outing with Pat Barton, who introduced me to Olivine, I had become enamored with a big oval piece in an embankment a hundred yards down river and on my way to it I walked by a stone which he immediately stopped and started prying out from between the rocks in a frequent scour zone. The result was his piece Nooksack Dream.

The stone I had my eye on eventually became the piece “Bound By A Common Future” installed in the Evergreen Arboretum. It took Pat and I almost a half a day to get it loaded and bring home, taking it to a symposium, and more than three years of occasional work on my part to reveal and refine before completion.

The intuition of a connection to a stone can be difficult to describe, especially why you choose it, how you might eventually carve it, or why it seems to choose you to find the form within. That moment in time, that choice, is the sum of all your past experiences and your hopes coming together in an encounter, which can be inspirational and awesome. It changes what you do with your time, energy, and these few breaths you have been granted in this life.

Seeking stones is a path worth following for many reasons. When taking the time to listen quietly, carefully, and reflect, much can be found within.

We need some kind of descriptive text here.