Elena Engelsen is Norway’s foremost sculptor of animals. Modeled in clay, and executed in stone or bronze, Engelsen’s animal sculptures invite us to look at the physical particularities of their species – the shell of the armadillo, the stance of a watchful lizard – and to experience the singular animal’s existence and vulnerability at the same time. Her sculptures evoke compassion, not sentimentality or an anthropomorphic emotionality. They challenge us to understand more about each species and the infinite diversity of nature – from the giant bronze tiger outside Oslo’s Central Station to the curled up little mouse in stone, a snail, a crocodile.

Gallerist Bjorn Li writes about the vulnerability in Elena Engelsen’s sculptures, “Never previously has a creature such as Engelsen’s Tube-nosed Fruit Bat appeared in art, suspended by its claws, the bat is depicted with its wings wrapped around its body, while the green eyes shine, sphinx-like, from an unprotected head, having none of the Egyptian sphinx’s authority, it is vulnerable to attack by its enemies even as it is suspended within the parody of an armour.”

Interviewed over the phone, Elena is warm, charming and down to earth, and generously willing to share her experience as a sculptor.

TØ: How did you get started as a sculptor?

EE: I’ve had a strong feeling for the materials since I was little. My father was a wood carver, and my two sisters and I got involved in the carving process very early. I interned at the School for Art and Crafts in Oslo for a couple of years, before I moved to the Netherlands and learned to carve stone at a stone carving business in Amsterdam. They started me out pitching corners for building stones. All we had was an angle grinder; everything else we did by hand. It was heavy, but really fun.

TØ: This is interesting for us here in the States, since we tend to use large power tools.

EE: I was fortunate to learn a craft, to learn techniques for carving right, “with air in your arm pits.” I created small models in clay, and learned how to enlarge them by two or three sizes for stone; using midpoints and sawing into the stone with an angle grinder, and then pitching the form.

TØ: You were in effect an apprentice?

EE: Yes, and I learned how to carve inscriptions, which has been a great benefit. When I returned to Norway after seven years, I got work at a gravestone company in Oslo, and did stone lettering for a living. When I got together with Per Ung (TØ: established Norwegian figurative sculptor), he encouraged me to quit the job and concentrate on my own work. We have been married for many years, and have worked together on large public projects. He also encouraged me to do molds of my stone sculptures for bronzes, to make a better living as a sculptor. Without him, I am not certain that I would have dared to do it, because I was insecure about my own work.

TØ: You have exhibited since 1977 and your commissions are all over Norway. What has it been like for you as a woman sculptor? What about children, for example?

EE: Per and I have a son who is 22 now. When he was little, I was home with him and modeled clay at the kitchen counter. As he was growing up, I adapted to his schedule and worked a few hours a day. To me it has been a very positive experience to be a woman sculptor. Of course, it’s easier for men, physically, but we have tools now that help us.

TØ: You still work mostly by hand?

EE: I use the angle grinder, but I do almost everything else by hand. Polishing. Especially with wet-dry paper which folds beautifully in your hand. My sculptures are too detailed; they don’t lend themselves to Alpha tools. It is better to do it by hand. But it has destroyed my arms, somewhat. Modeling in clay can give you problems, too, with tendonitis. Though working on the PC is worse, isn’t it? I did start using pneumatic tools, which made everything easier, but took some of the charm away.

TØ: It’s easy to lose some of the intimate, direct connection with the stone that way.

EE: Yes. Since I am not concerned with being faithful to the model, I like the way the sculpture is formed and keeps changing while it’s underway. Stone will have its own expression and you adapt to the stone and its structure and what it gives. We need to let the stone talk for a bit. It has to be part of the expression and the decisions.

TØ: What kind of stone do you use?

EE: I use softer stones like marble, and also a Belgian/Irish stone called hardsteen, which is calcified clay. It comes from under the ground and it smells a little bad, but it gives great variety of color depending on how you polish it.

TØ: Do you use a model every time?

EE: Always. I travel to different zoos, perhaps with an idea in mind, and model the clay model based on what I see. I also have a whole lot of books about animals.

TØ: Why animals?

EE: Because it is what I feel that I am good at. There is so much texture and tactility in the animal world. I grew up with animals and feel connected to them. Where I grew up, there were horses and dogs, and farm animals. My sense for exotic animals was awakened when my parents brought home a turtle!

TØ: What about sculpting people?

EE: I tried, but I prefer animals. I call myself an animalist. You feel it, what your strength is, and what you are good at, what you lean towards and what grabs your attention.

TØ: What is next for you?

EE: I have some private commissions, in bronze.

TØ: Are people more interested in bronze than stone?

EE: People know that stone is original, and costs more. Also, bronze can be repaired more easily if anything happens.

TØ: In the States it is now more common to have bronzes done in India and stone in China.

EE: That wouldn’t work for me; I need to work in the mediums. I never use assistants. I do all the work myself in stone, and I work directly with the foundry. You need to go through the process.

TØ: Would you say that you are moving more towards bronze?

EE: Yes, it has to do with the fear that I could really hurt my arms.

TØ: So many people ask how long it takes to complete a sculpture.

EE: I once carved a sculpture in a summer, 7 to 9 weeks. It is a slow process, but it is important to be impatient. You can’t be too patient when you work with stone! It is no fun to get stuck with a sculpture for years – get it done.

TØ: Are there any animalier sculptors who inspire you?

EE: Rembrandt Bugatti, who worked in the zoo in Antwerp. He is my great hero. We work completely differently, but I admire him.

TØ: Your animal sculptures are soulful. You show some of them resting, but th

ey look as t

hough they are about to awaken. There is so much motion in your sculpture.

EE: It is important to me to express their vulnerability. Like the Armadillo: It is secure inside the shell, but it falls asleep and you see how vulnerable that makes it. You see it in the gaze of animals, and it’s important to study the mimicry and try to express that.

TØ: Do you have animals yourself?

EE: We’ve had cats and dogs, now I only have two old cats.

TØ: What kind of advice would you have for people who work in stone?

EE: It can be difficult to make the choice to become a sculptor. Yet, for some it is just something thatyou have to do, it isn’t a choice – it is your way in the world, and you don’t think much about the alternatives. It is who you are, what you have to work with. When I was a teenager, I was so certain that I was never going to do anything in art, and here I am …. You have to believe in yourself and what you do. Getting encouragement is important. What you do may not appeal to others, but you have to stick to it. You know the feeling when you “get” it and it’s flowing.

To see more of Elena Engelsen’s work, go to www.elenaengelsen.com

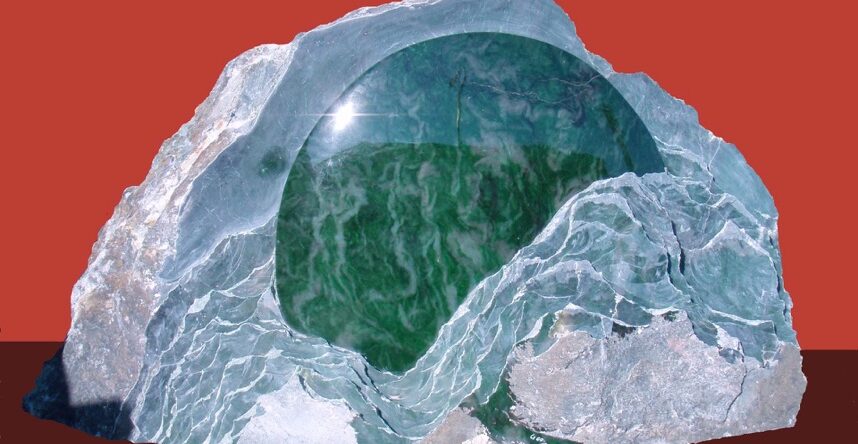

We need some kind of descriptive text here.