This is an interview with sculptor Brian Berman at his new home and studio on Bainbridge Island, Washington. Already prolific artist, he seems to be entering a new level involvement in his art with a large commission to be complete this year. And he is starting to work in monumental scale. He even has a new (pre-owned) one ton flatbed with boom crane. Large pieces of basalt and granite await his attention around his wooded yard, as well as an array of other smaller stones. We start by viewing his model of his recent commission for an outdoor sculpture/fountain to be sited at a Palm Springs area residence (see cover photo). It is a l/6th scale model in plasticine, of woman and child The woman will be pouring water from the urn she holds into another urn on the ground A child stands beside her, holding a bowl. The main female figure will stand approximately 6′ high and both figures will be carved from Indiana limestone. The “base” area will be approximately 6’x6′ and simulate a dry riverbed.

SS: Brian, why is the large figure developed with more detail, while the smaller child-form is generalized?

BB: I had trouble with the concept of the child. I didn’t know how old the child should be, what type clothing or anything. So I minimized the child-form and did four renditions in different positions. I showed the client the three options, but she liked the original form. [We look at child-form options.) Initially I was asking, “How are the figures interacting? What is the relationship between the two?” And in any kind of interaction with water, there’s usually some function that’s taking place: bathing, drinking, hauling water. I was trying to develop some kind of purpose. Then I got into the mind of the child and thought, there’s also playfulness. So I posed some of these options in a posture of playing or receiving the water from the mother.

SS: Had you previously done work for this client?

BB: Yes, she purchased a granite water basin at a show on the island. It was a form (in the basin) based on the Native American raven-head archetype. That happened to be a form that was very significant to her.

SS: Do you feel that kind of communality with her about the large commission piece?

BB: This felt more like a contract She suggested the theme. Also, I wouldn’t have chosen to do it as a fountain because of the complexities of adding that element to a sculpture that could stand on its own. The challenge of this job was she wanted me to give her some costs. She wanted me to give her a presentation prior to agreeing to anything beside the general theme. In my first proposals, I presented an 8′ heroic size. She said she was thinking of 4′ high. Being prepared for that meeting, I showed her what that height would look like at a distance and noted that this piece is going to be seen in perspective. She then agreed to a 6′ high piece. I had made a price chart for myself, starting at 3′ up to 8′ tall. For every one-foot increment, I calculated what price I would charge to carve a sculpture in that size with minimal detail. Then I figured how much I would want for the stone, showing a difference in price for different types of stone (limestone, marble or granite). I made granite the most expensive because it would be the most challenging to carve. Marble was next and finally limestone. Then you have to add all the extra costs including moving a large stone, crating, installation, sitework delivery, etc.

SS: [We look at Brian’s presentation material – a collage of images including a photo of native people with their children and three sculptures in “Native American” style dress.)

BB: The client wanted the piece to have some “native” appearance. I first went for portraying “native mother and child.” In the initial meeting, I had the piece bid out as if the two figures were connected as one stone. But she clearly wanted the figures to be separate. The discussion with the client started by her saying she was inspired by “The Water Bears” bronze sculpture in Kirkland, Washington. So that was a lead idea. Then she said she wanted two figures standing by a stream in her yard, which included making the stream. So to go into the meeting and come up with a contract, I went in with several photo montages done with “Photocopy” software, which combined and altered several images to approximate the sculptural proposal in its environment This amazed her. She could show these to her landscape architect This was all done prior to any contract or payment I didn’t have a design-phase contract

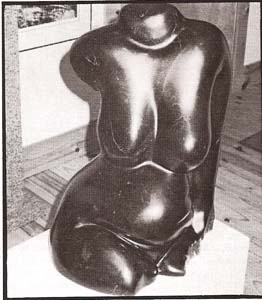

I came across a retrospective book of the work of Allen Houser. I saw these images an d realized this was the artist who has fully captured the inspiration of what this piece could be. He was like a mentor to this commission happening. I have no cultural connection to native people. I needed something to connect me with their art. When I saw his work, it inspired me. That then led to me carving, at the Vancouver Island Symposium, this most recent piece (approximately 20″ x 15″ x 12″ entitled “Proud To Be Me” – a native woman seated with a water urn, wearing beads, and carved from chlorite. This person just “showed up”. I didn’t do facial studies; I direct-carved it. After doing the research around the commission, there was an impression made in me. I just went out and I carved She has that look of being proud to be who she is. I will also use the direct carving approach to this commission instead of pointing up from an exact model.

d realized this was the artist who has fully captured the inspiration of what this piece could be. He was like a mentor to this commission happening. I have no cultural connection to native people. I needed something to connect me with their art. When I saw his work, it inspired me. That then led to me carving, at the Vancouver Island Symposium, this most recent piece (approximately 20″ x 15″ x 12″ entitled “Proud To Be Me” – a native woman seated with a water urn, wearing beads, and carved from chlorite. This person just “showed up”. I didn’t do facial studies; I direct-carved it. After doing the research around the commission, there was an impression made in me. I just went out and I carved She has that look of being proud to be who she is. I will also use the direct carving approach to this commission instead of pointing up from an exact model.

[The conversation turns to some recent changes in Brian’s life.)

BB: My life as an artist bas been very hand-to-mouth. The importance of my story is that when I’m doing my heart’s work, it isn’t about the money. It’s about being happy that I’m able to live and work doing what I love to do. It isn’t about how much I’m selling the job for; it’s that I’m going to be supported for the length of time it takes to make this sculpture (a year-long project). Last year was truly a “phoenix” year for me. There have been many “crash-and-burns” along the way. Up until the end of ’96, I was basically without a home for six months. I was houseboating. I always had a place to live and sleep. For several years prior to that, I’d been living in other people’s homes in creative ways. I was a caretaker or remodeler or I sublet. It was really difficult to move my career forward without a base. It took finding this place and the benevolent landlord I have to obtain a base to operate from. And the day I moved in, he said, “Let’s find you a place to work” I’ve had a year of grace. The studio was built with only one purchased piece of wood. Right after I got started, I was given a barn to take apart which had all the wood I needed.

SS: There seems to be a lot of serendipity going on here in terms of taking your next step in your career as an artist.

BB : Yes, there is something important here. Living as an artist, without any means other than what I create with my hands, it’s difficult to meet financial demands. But a friend was asking me about my dream of the life I wanted. I said I want Bainbridge to be my home and community the place for me in my career as an artist It was like going to the fortune teller who says good fortune is going to come and then says, “Let me write you a check.” My friend said he knew of a place and set up an appointment which led to me living here. And he also donated all the 2×4′ s for the shop.

I’m reminded of Bill Moyers interviewing Joseph Campbell and asking about the notion “follow your bliss.” I had some pretty dark moments. One day I was channel surfing on tv and came upon Campbell saying something like: “If you go through your life being a good provider and you had artistic inclinations which you didn’t express, you’d look back at your life and have regrets. But, if you have artistic interests and you’ve expressed them, you’ve made a gift to the world. Live without the money if you have to. Give the gift.” That message affirmed my artistic conviction.

SS: How did you transition out of your previous life?

BB: This was my phoenix myth. I had created a marketing business making promotional sportswear and awards. I loved that work I love providing things for people. I love producing things. These were custom made items mostly for nonprofit organizations.

But things fell apart. This involved a three-year litigation with a partner and a debt that drained all the life energy out of me. I didn’t want to do anything in business ever again. That was the “dark night.” I felt like I had “done it”. I had wife and kids, my own home, a successful business. I had done all those things. That life is over. I felt extreme pain and shame about that loss; besides losing the business, my marriage had broken up, I’d left the home, and was estranged from my children. Out of those “ashes,” I have been the only thing that felt good. I was grieving. I didn’t building my life as an artist since ’91.

SS: What was your art background and work history? Obviously you had a creative business.

BB: I have no formal training. I’m self taught in most of my handiwork I learn by watching and doing. I took a job at a large pottery equipment manufacturing company run by hippies. I fit right in. This was a phenomenal environment They hired me as a welder; I didn’t know how to weld. I learned many things by doing. I cast concrete, sandblasted, bent pipe for frames, ran metal lathes, ran a punch press, wired electronic components, and worked in the repair end Eventually I became the purchasing agent, which was one of the most-fun jobs I’d had, with a two-million-dollar budget to buy parts and material. We were constantly developing new products. It was fascinating to go from an idea to acquiring materials to creating the product – much like sculpting. After seven years, I was eventually offered the General Manager position. At that point I resigned because 1 needed to create my own business. I created a promotional marketing company. We made pictographs, buttons, decals, T-shirts, posters and went into the national gift industry. This eventually became an $800,000 per year business.

SS: When did you start creating art?

BB: The discovery of sculpting and working with stone came out of my unconscious. When my lawsuit ended and I had lost my career, I was deeply depressed and I needed something to do with my son Jay other than watch television. I went into an art supply store where they had a promotion–if you bought the set of riffler files for $35, they gave you 20 lb. of soapstone. Jay and I started carving, day after day at the kitchen table, eight hours a day, telling stories, making up techniques. Jay returned to school and I kept going. I found it was the most sane thing I could do with my life in that state of mind. It was the only thing that felt good. I was grieving. I didn’t realize how much grief I was holding in my body until I carved a piece called “grieving man.” That made me aware that I could express myself artistically. So I sculpted as a healing process for the next year and eventually went to my first stone carving symposium in ’92. I was totally thrilled to meet others who were into the therapeutic nature of sculpting. I wasn’t looking at it as making art. I was doing something that was keeping me alive. That was what was real I wanted to infuse myself in the stone and see what happened. I carved “The Peace Guardian” in alabaster-a dove in flight protected by a ram with horns. Sculpting became a process of protecting me.

SS: You’ve been teaching beginning carvers at the various symposia for several years. How do you see the teaching process and yourself as a teacher? [Brian has also been NWSSA symposium coordinator for Camp Brotherhood and Silver Falls, Oregon, for four years and two years respectively. He has been on the carving faculty for the Whidbey Island Retreat for two years and he will teach “direct carving for beginners” at Camp Brotherhood in the summer of ’98.]

BB: I’ve always enjoyed sharing what I know and am enthused about I also teach at my studio (spring/fall) in weekend sessions. I create a supportive environment that allows people to explore their creativity. My purpose is to share the joy of carving stone.

SS: What is the ideal state in which to do your work?

BB: For me the ideal state is when I become “transparent”: the activity is happening and I’m the instrument that makes it happen. All my faculties are engaged in the process, but it’s a timeless process–nonrational When days go by like that, I wonder: how did I get this far along? I don’t remember going through all the steps to get to the finished sculpture. [We look at several pieces around his home.) Very often when you’re working in that direct carving mode, you start with one idea and something else will emerge. You realize where the “energy” is for you – how you are connected to the piece. You realize where you want to take the piece, what direction you want to move in.

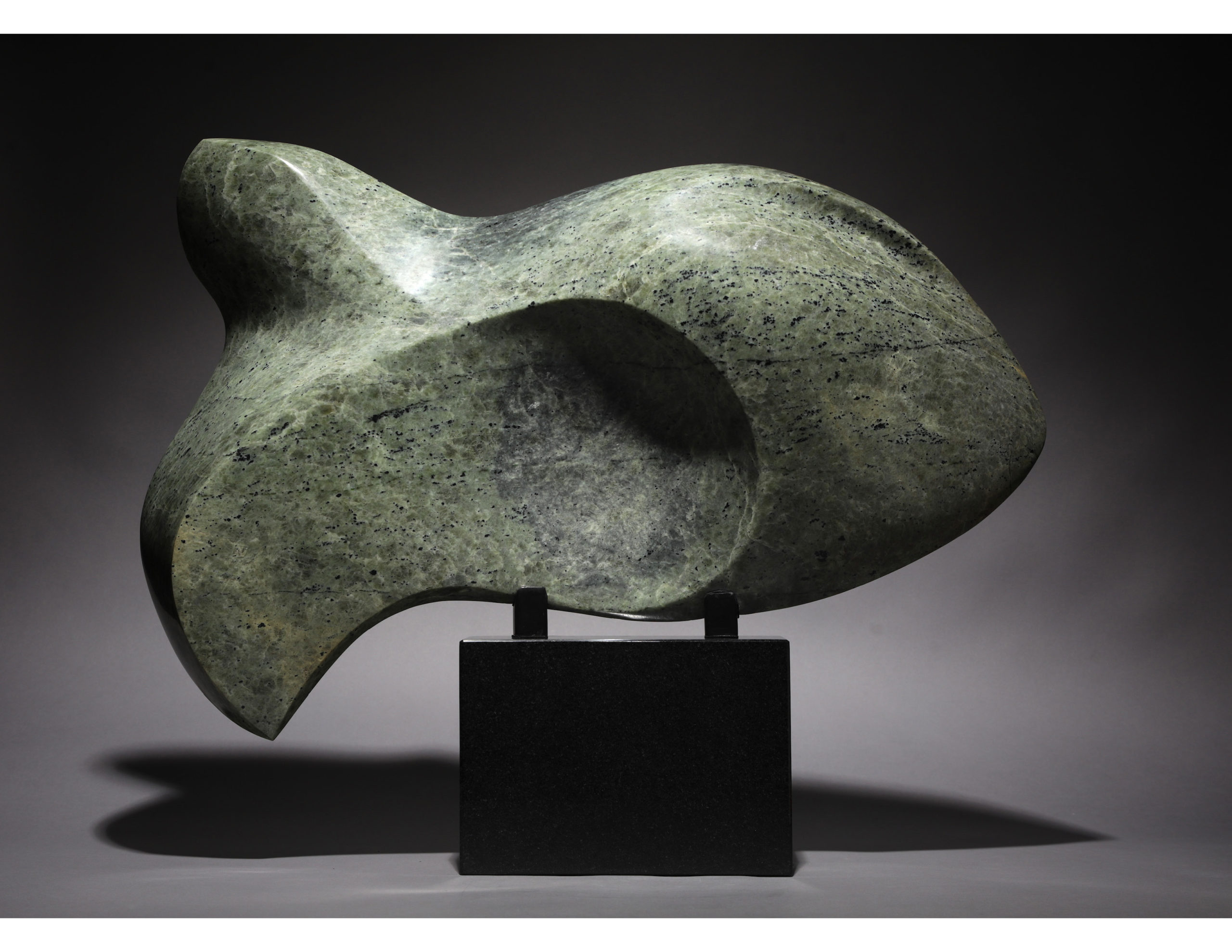

[We look at an award-winning sculpture in Wenatchee soapstone entitled “The End May Just Be the

Beginning of Something Else” (’94)]. This was another part of the completion process. I was working with the theme of beginnings for a theme show and I started carving fish tails. It was very metaphorical, about endings also being beginnings. I often use what I call “journal in stone” because I write stories about the pieces that are displayed \\ith the piece. These are about how they relate to the phase of my life I was in when I carved the piece. I’m not sculpting just to make salable pieces.

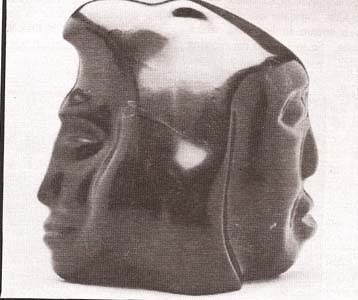

[We look at his “A Shaman’s lnitiation”-a head form combined “with a bird/raven head in chlorite, finished dark black] I carved this piece after spending a week with a Siberian shaman trying to understand shamanism. The sculpture illustrates the transformation into the shamanic world. [We talk about his “functional art.” He has created an array of stone vases, puzzles, and necklaces. He talks about how his experiments with interlocking puzzle pieces and vase forms led to smaller “tantric beads” with interlocking stone elements which he makes in a series for shows. He also shows me his sculptural “perfume bottle” designed to hold and dispense fragrant oils.]

SS: What percentage of your work is the more functional art?

BB: Maybe 20 percent That will be different this year with the commission.

[We go out to his studio and talk about his 7′ high, 1800 lb., granite form, entitled “Mudra: Peace Monument: and slated to show at the Seattle Flower and Garden Show. His initial plan was for a piece with minimal shaping, taking advantage of the natural stone shape. He then considered working it horizontally and adding leg elements. The most recent idea is to develop it more fully as a composition: an abstract figure in dancer posture, incorporating the mudra hand gesture.]

SS: How do you use the direct carving approach with a piece this big?

BB: I work around the piece as though it were a smaller piece. As I work, there is an internal inspiration about what to do. If I think about the monumental significance of the piece, that tends to suppress the creativity of the moment. With direct carving, there is always a “dance” between planning and inspiration in the moment in which the piece evolves. Ideas “show up” along the way that enhance the design. I’m working for something that resonates with me. I ask, “Does it please my eye? Does it say something to me which correlates to something meaningful?”

Working large in the direct mode is a way of saying, “Here I am,” in a way that can’t be hidden. And it’s part of my evolution of emerging from the cocoon of self healing. It’s not important that I “understand” what I’m creating right away.

SS: Thank, Brian.

We need some kind of descriptive text here.