History

I grew up in a family that was fairly clear that “art” was something that other people – people with talent and skill, and drive – did. So it’s hard for me to take on the mantle of “artist” without feeling a little like an imposter. It’s through my involvement with the NWSSA that I can engage in doing this thing that I love and occasionally emit something that’s almost, but not entirely quite unlike, art.

As a youngster, I used to carve bars of Ivory soap until my mom got tired of me leaving soap flakes in the den. When it came to art, I always tended towards 3d craftwork like clay and plaster, but I also got involved in silk screening, tie dye, music, and other hippie activities. I grew up in Vermont, surrounded by marble and granite everywhere. We even had a marble erratic the size of a house in our backyard, and our village sidewalks were cut marble slabs. Still, it never occurred to me to try and shape the stone until…

Starting with Stone

I first encountered real stone carving in a weekend course held at Rich Hestekind’s studio in Preston. He showed us how to carve Tenino with hand tools, and I fell far, far down that rabbit hole. His clear enthusiasm for the craft and genuine interest in and support of his students was truly a gift. After two days of slow going with hand carving, Rich demonstrated some of the power tools that we could use, like pneumatic hammers and diamond saws – tools that could move just as much stone in a few minutes as we moved all weekend.

My eyes got huge, and I immediately wanted to try my hand.

Rich’s direct encouragement of my efforts was something I could hang onto as I stumbled through a few smaller projects at home. My first pieces were soapstone cats, sandstone chili peppers, and limestone architectural elements. I soon bought a pneumatic hammer kit from Trow & Holden, but it intimidated me.

And yet, I wanted more.

The summer after the course with Rich, I attended Camp B for the first time.

The Symposia

My first symposium was in the late 90s at Camp B. I was a complete novice and encountered some challenging stones that were painfully frustrating: an Alaskan marble that turned to sugar just as it neared the shape I wanted, a hard and brittle limestone that always seemed to fracture in the complete opposite direction I intended. I was humbled by my failures and grateful for the incredible sense of community and support in the camp.

Carvers of all levels stopped by my tent to see what I was doing, ask questions, and make suggestions. Each one had their direction or interpretations but was invariably positive and supportive. Advice like “free the head, and the body will follow” (Alfonso) and “get the excess stone out of the way so you can see what you’re doing” (Sabah). Walking around to see other carvers use their tools helped me get over my fear of the pneumatic hammer, and the generosity of people lending their time, expertise, and equipment helped me deepen my connection – to the art, to my curiosity, and to my confidence in learning through experimentation.

That was when I learned what sculptors mean by “having a dialog with the stone.” With real stones, there are soft spots, hard spots, cracks, and joints, and all these must be reckoned with to get to the finished form. Like many stoners, I have a yard full of potential sculptures and must listen carefully to learn what these rocks want to be. I’ve talked to many stones over the years (and they have to me), and I can assure you they all have opinions. Some have attitudes, some are vain, and some are exceedingly indulgent (I’m lookin’ at you, pyrophyllite). My question is usually something like, “how can I let the beauty of this stone out for all to see, touch, and experience?” The stones, for the most part, are usually open to this.

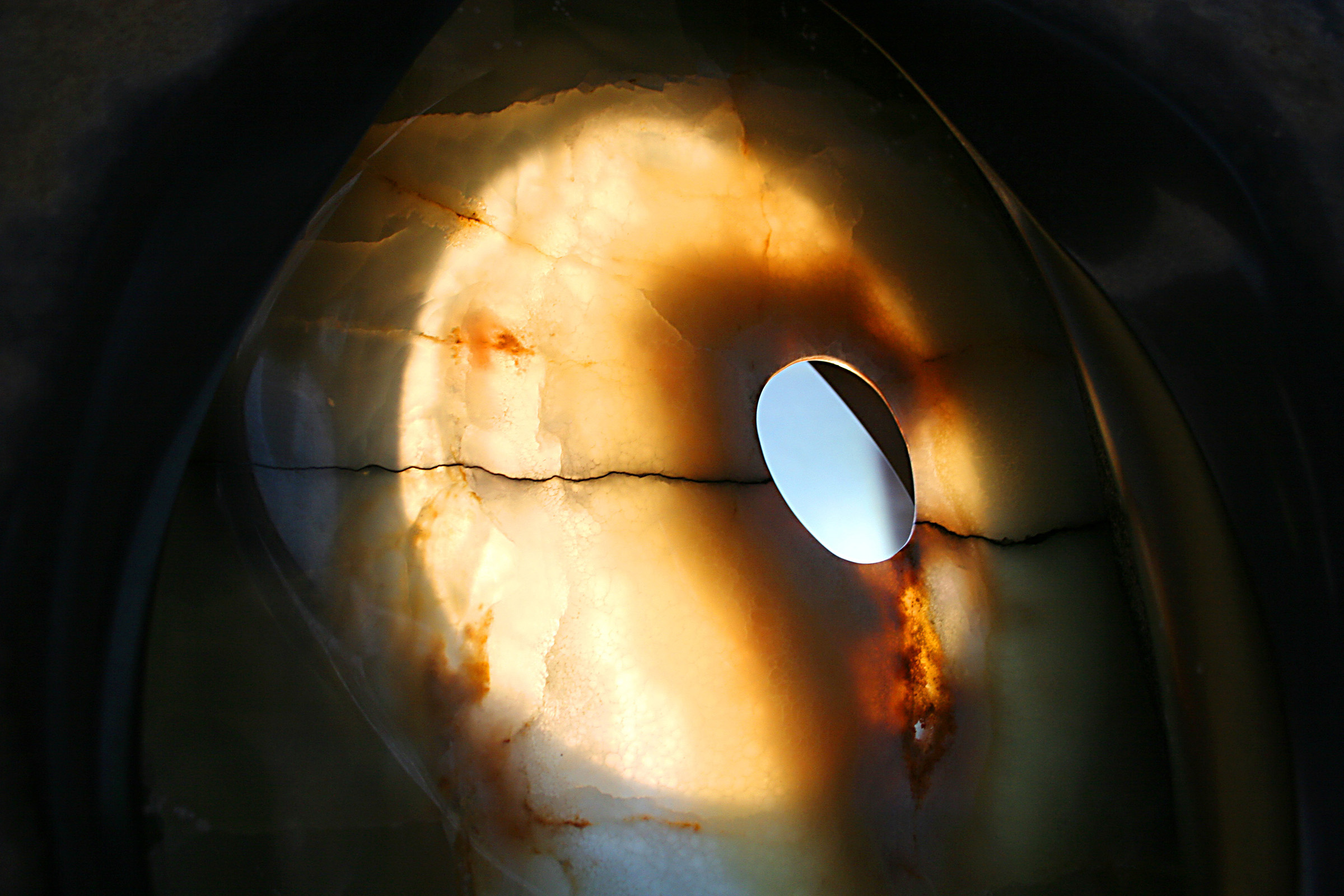

It is this thing, the essence of the stone itself, that I want to share with the world. The beauty of backlit honey calcite, the velvet feel of marble at 400 grit, and the shine of a well-buffed basalt. If I were to have an artist’s statement, it would be: “Here. This. Touch.”

I work on small and large scales: as small as rings and necklace baubles and sometimes as large as myself. It used to be my only limitation were rocks I could physically move on my own, but an on-going partnership in a crane truck has broadened the scope of sizes I can work. I love making bas-relief and fully three-dimensional pieces.

I share some of my work as a guerilla artist, leaving carved stones in people’s gardens in my neighborhood. Sometimes they remain untouched for ages. Other times they disappear. My favorite is to see them moved, propped upright, or otherwise featured in the garden.

Process

I read once that humans are wired in such a way that if there’s a bend in a road up ahead, we want to find out what’s around it. As I work on a sculpture, there’s always a corner to go around, and I always want to see what’s next. Often when I am working on a piece, my thoughts will keep returning to a person or event from my life, and it’s this artistic and physical activity that helps me process that memory and, sometimes, incorporate that into the sculpture.

Carl Nelson shared a Ken Barnes observation with me: “some people lick the stone until they find what they are looking for, and others prefer a more direct approach.” I’m a licker. I love the whole process and the measured discovery of the final shape, and I kind of want that sense of discovery to go on and on. I realized I deliberately choose complex designs to spend more time on a piece (like detailing every sucker on a sleeping octopus).

The entire exercise gets me into the flow, where I lose time and my everyday woes melt away. It doesn’t lend itself to building a large and varied portfolio, but I’ve come to realize that I’m not in it for the number of finished pieces but more for the quality of the experience along the way.

A decent part of my experience is having a nifty studio space, somewhere comfy and inspiring, where I can create. I’m constrained by space (and noise ordinances) at my home, so I look forward to the symposia where I’m not so confined. All year long, I think about how I’m going to pack all the stuff I’ll need into an increasingly smaller space just for the sake of efficiency and order. My dream is to have a tiny origami box that unfolds into a fully functional studio.

This past year my son Jake joined me at the symposium and spent a couple of days carving in the beginner’s tent (I’ll let him share his own story in a future Sculpture Northwest edition). It was an honor to share my passion with him, and I think it was good for him to see exactly what was so enticing about this thing that I’ve been coming to every year his entire life.

Thanks, NWSSA

Without the association, I’d still be afraid of my pneumatic hammer. I wouldn’t know anything about finishing, polishing, pinning, siting, or presentation. I wouldn’t have found a couple of equally obsessed carvers to go in on a crane truck, and I’d still be leaving soap flakes in the den.

We need some kind of descriptive text here.