This is an interview conducted by e-mail and phone with Elaine MacKay. She has been a member of NWSSA since 1996. Where she lives says a lot about her character and also the type of stone she uses for many of her pieces of sculpture. Twenty-five miles southwest of the Columbia River and in the small town of The Dalles, OR, Elaine and her partner, Pat, live on 40 acres of land on the lower slopes of Mt. Hood, with National Forest land on one side and wheat fields for miles on the other, and lots of beautiful basalt in all sizes and shapes for the taking. They have built their own home, using native stone for much of the structure’s interior. Self-reliance and hard work are very much a part of living in a remote area.

AN: Who are you and what is your history as an artist?

EM: The question, “Who am I as an artist?” might more correctly be titled, “The Road Not Taken” and begins back in 1968. I had transferred to a small liberal arts college at Mt. Angel, OR. This was my first exposure to art. Coming from a red-necked background in farming in a small Eastern Oregon community, WE DID NOT DO ART! At Mt. Angel I had to pick a major. I really wanted to go into art because I worked with my hands all my life, but the ageold question at the time was “what are you going to do with a degree in art” and having a very fragile ego, I picked English instead. But every free moment I could find I spent out in the Art Dept. I made handbuilt pots, fired in the Raku method, in a kiln we all built in the side of the hill. We spent long hours collecting clay from the river banks and mixing our own glazes, then firing late into the early morning hours, flames soaring over our heads. A very mystical experience and one I’d never forget through the intervening years when I involved myself in homesteading and various pursuits aimed at earning a buck. I did not actively engage in art again until 1996.

AN: How did you get back into art?

EM: Just a very lucky chance! Vic Picou came to visit a friend and neighbor of mine here on the Ridge. Although I didn’t meet him at that time, my friend Jim told me he was a stone sculptor. I nearly went bonkers! I have always loved stone, hauled em’ up from hell at times. I stacked ‘em and placed them and ruined many a good one because I didn’t know what I was doing, but I never did any pure art. To make a long story short, I phoned Vic, he mentioned Camp Brotherhood, and it sounded like a wonderful opportunity and Vic assured me that I would be welcomed. I was! I call it the summer of my rebirth. Here I was, surrounded by all these wonderful people, a little intimidating, yes; BFA’s, MFA’s and more A’s than you could shake a stick at, but folks would come over and ask me what I was doing and say “Cool.” Like pouring water on a plant dying in the desert. Wow, what a wow! What a group of people! This event coincided with an article I had just read entitled “The Long Sleep” from a book by David Quammen. It dealt with the extinction of a species, in this case the Dodo bird. Being alone, having no one else of her kind, being rare and through a complicated synergy of links is pushed into extinction by death. It was how I felt before Camp Brotherhood ’96. Then I discovered NWSSA and I knew to the depths of my soul I had found my life link. So I went back the following year and began my pursuit of knowledge of manipulating stone.

AN: Why is art important to you?

EM: Because I have spent many years being a frustrated wanna-be artist. Believe it or not, I didn’t know there was such a thing as stone art, except in history, until Camp Brotherhood. Furthermore, art is important because it is the most individualistic and unique expression we can offer of ourselves. Stone art in particular is, I think, the kernel of all art because our ancestors manipulated stones long before other art forms.

AN: What is your philosophy of art

EM: The short answer is don’t ruin a good stone, because inherent in the stone’s form, color and hardness is the possibility that the hand of an ancient may have touched it. This philosophy is of course easy for me because I carve basalt. The philosophy is in the stone, i.e., what I imagined an old ancestor might have thought of it, why they might have picked it o

AN: What kind of art do you create and from where do you get your ideas?

EM: I do not have the intrinsic ability to look at a block of stone and say I see so and so in it. I go searching for forms, I spend a lot of time and bloody fingers doing so, but it is also an integral part of my process of carving a stone. I imagine when I go stone searching. I imagine my clan long ago fingering the same stones. It is a link to our ancestors older than all others, older than any other art form, they could have touched the same stone as I, they might not have but they could have. My forms and what I do with them reflect what I feel my ancient ancestor also shared, images of pleasure, healing, power, protection and an awe of the mysteries of life. He found joy in the stone at the river bank and it caused him to have pleasure whenever he looked at it so he lugged it back to the den.

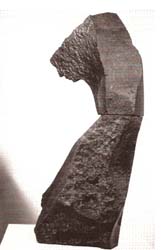

What kind of art do I create? Primitive would about sum it up. Sometimes I don’t do anything to the stones I have at home. Never ruin a good stone. So if I go doctoring a stone I follow the philosophy above.

AN: What type of tools do you use?

EM: I use mostly air tools, as I did body and fender work for 10 years and am familiar with their use and you don’t have to worry about getting zapped, as I use water a lot in my grinding and cutting It keeps the dust down and lubes the blade. There is of course a place for hand tools also, as Reg Akright pointed out. I intend to incorporate them into my tool collection in the future. Money! I like pitched surfaces and again it’s the primitive act of striking that appeals to me.

AN: What scale do you like to work in?

EM: Well at this time, pieces that I can tote. Though I am sifting every thread in JoAnn Duby’s brain on basing. With multiple basing you can achieve soaring pieces that you can still lift and move without breaking your back.

AN: What new and wild ideas do you have planned for future work?

EM: With the multiple basing thing I am going to work on a series of shape-shifters this summer. Pinned and sleeved, each stone can be turned independently of each other and thus a different face, hence shape-shifters. Again this goes back to the old ones and the mythology of the Native Americans and Celts.

AN: How many do you work on at a time?

EM: I work on several at the same time. The first 15 minutes on most pieces is ecstasy and then you can get bored, push something that you shouldn’t and not allow the stone to be and can just and up destroying a good stone. So I rough out a bunch of what would be considered ideas then “I just sets em’ about and ponder em.’”

AN: Where have you shown your work?

EM: At this time , I enter most shows NWSSA puts forth in the newsletter. I haven’t done the gallery thing because I do not have a big enough body of work at present. Hopefully that will come; I have received immense satisfaction in the short time I have been carving stone. I won an award at the AIA show last year in Seattle, which left me speechless. I also had a piece accepted at Big Rock Gardens in Bellingham for permanent exhibition and am in tremendous company up there. Even though it was a long distance to bring work, I have two pieces in the Bremerton Show.

AN: Is there anything else you want to mention before we close the interview?

EM: Carving stone has given me personal happiness, satisfaction and an even keel in my life that had heretofore eluded me. Which brings me to the importance of NWSSA in my life. The community of like-minded people, ideas, education and opportunity. Reading David Quammen’s article on the Dodo bird coincided with my first Camp B. symposium and I knew I would never have to face such a destiny. This is what my art and the people I absorb through NWSSA gave me. I hope I am able to give a tenth back.

We need some kind of descriptive text here.