Home » NWSSA Events » Shows » Past Shows » Adventures in Stone: Stone Art at the 2000 Tucson Gem & Mineral Show – May/June 2000

Nothing compares to the Tucson Gem and Mineral show. It is the largest show of its kind in the world. The variety and sheer volume of minerals shown is astonishing. Vendors and buyers fill the city’s coliseum and every motel in town. From the beginning, its primary emphasis has been crystallized mineral specimens. The Smithsonian, the Sorbonne, and other great museums exhibit their mineral treasures there. Fossils for collectors and stone for the lapidary arts have long been incorporated into the show. Stone for sculptors, and stone sculpture itself, is relatively new to appear.

Ed Klotz, from Phoenix, began to exhibit his free-form table sculptures there about 20 years ago. In 1996, Ed bought the first piece of Aphrodite marble I ever sold. The following year, as I had the good fortune to stand by and watch, Ed sold a fine abstract made from that very stone. (Sculpting until past his 90th birthday, Ed died in 1998.) Another early-appearing sculptor at Tucson was Paul Hawkins, of Camp Verde, Arizona. Known for his alabaster sculptures, his stone art was recently featured in the Lapidary Journal. Paul produces two types of work. Most notable, his fanciful, Dr. Seuss-like creatures are compositions of colored alabasters that stand three or four feet high. Paul says he has sold, altogether, about 10 of these playful pieces. To whom? Not to kids. They are far to delicate and vulnerable (and “pricey”) for the playroom. Offering only a shrug for explanation, he says “shrinks” buy them. Paul’s bread and butter item is the alabaster bowl. His bowls feature lids with finely inlaid colored stones. Paul asserts that the buyers at Tucson – “Americans in general” – are most apt to buy “functional art.” Pointing to his bowls, he says: “tell Martha it is something pretty to put on the table but tell Ralph it is something he can put his 30-30 shells in.” Tucson is not a fine arts market in Paul’s estimation; still, he thinks, it is still a good market for stone art. This is because the visitors to Tucson appreciate and understand stone. “Unlike the gallery people, they recognize the amount of work that goes into a finished piece.”

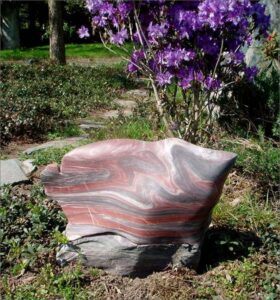

The Tucson Gem and Mineral show is not a good venue for selling most raw sculptural stone. Because the bright hues of the lapidary world are most visitors’ frame of reference, only colored marbles sell well – the Jupiter and Aphrodite from Alaska, the Rainforest from B.C., the Picasso from Utah.

I introduced the first two there. Rainforest is now too uncommon to be sold much there or anywhere; Picasso is abundant. The Picasso comes from three or four different quarries located near Delta, Utah–I have heard “all on the same mountain.” Some finished sculptures of Picasso were at the show. Pieces were either free-form, reportedly done by the daughter of one of the quarry owners (I apologize for not being able to report her name) or were carved in China. The Utah woman’s free-wheeling abstracts and the Chinese carved Buddhas were set side-by-side in the Utah quarrier’s display, the only common element being the marble medium. Next to each other, they seemed an extreme (if not jarring) contrast of style, a contrast that spoke not so much of different artists but of different national art cultures.

Chinese carvings were plentiful at Tucson. They can be recognized instantly. No matter the stone used–jade, rhodonite, Picasso marble–they seldom, if ever, stray from traditional Chinese subject matter. The dogs, horses, ducks, roosters, turtles, lizards, bears, fat and happy Buddhas all exhibit great technical skill. Regrettably, the very definition of a commercial product, they always appear the same. (I claim no expertise on the subject of Chinese stone art. You can take or leave the thoughts expressed in this paragraph as based on one person’s limited observation.) There was no individual variation in the Chinese stone art I saw, nothing–even in the larger pieces–that stylistically identified any one particular artist. All the Buddhas, all the horses, all the lizards, have the same stance, even the same facial expressions, even though many different carvers must have produced them. Perhaps the idea of sculpture as a medium of individual self expression is a peculiarly Western notion. Perhaps in China a good carver is not one who pushes the boundaries outward but is one who, oppositely, hones in on an ideal form. It is not a horse as it canters in front of the eyes or even a horse that races through the imagination that is carved, I believe, but a culturally codified, formalized image of a horse, an image ossified over the millennia of Chinese history. A look at that history might show, as explanation, that the exhibit of free will and imagination has often been poor survival technique for Chinese artists. The rampages against individualism (“a bourgeois and Western corruption”) that took place during the Maoist Cultural Revolution in the 1960’s are an obvious example. Artists accused of doing things a little differently were humiliated, degraded, and sent to the farm. Tiananmen Square stands as a more recent dis-encouragement to Chinese wanting to stray. Confucianism, the dominant social/political/philosophical system in China over most of its history, stressed order and obedience no less than modern communism. It too discouraged artistic experimentation. There has developed in China no free-wheeling artistic tradition.

A second notable fact about the Chinese carvings at Tucson is that they are shockingly inexpensive. One Chinese vendor had 10 stone lizards in a row, all carved from a pink marble much resembling the Chomondeley Pink from Alaska. The carvings were good, the polishing excellent. When I picked one up to examine, the vendor said “28 dollars.” I tried to imagine how a lizard, 10 inches long and of good detail, could be carved (and carried from somewhere in the interior of China, shipped to the U.S., trucked to Tucson, then displayed for sale with show fees, room costs, table rentals, and all else involved in that) for $28. As I considered the piece – all the labor that far distant human hands put into it – I heard the vendor, growing anxious: “Okay, I sell you two for 28 dollars.” Anyone out there want to do a detailed, 10-inch carving in marble for 14 bucks?

Into this milieu – of stone Buddhas (smiling from eternal China), of crystal and fossil collectors (gathering from everywhere for this mother of all mineral shows), of gem dealers and their cover-girl-beautiful sales women (flashing perfect teeth, gold, and mega-carats), of “new age” devotees from California and Sedona (talking of vortexes and feeling stones for properties no geologist can find), of museum curators from back east (wearing threepiece suits in the Arizona desert), of lapidarians from Oregon and the Southwest (wearing bola ties and licking agates), of a great army of all sorts of folks who like myself simply love rocks – comes Stone Arts of Alaska to do a firstever- at-Tucson outdoor sculpture garden.

The idea evolved last year from a conversation I had with one of the show producers. We found a fairly ideal spot in the courtyard of one of the motels central to the show. This motel, the Ramada, was primarily devoted to fossil collectors. Since I would be featuring works out of Aphrodite marble, which is fossiliferous, I thought the location appropriate.

Artists who had bought and worked some quantity of Alaskan stone were asked to participate, which was a way to support the artists who support me. Their work was acquired by purchase or trade or was shown on consignment. Aware that most visitors to the show would not be of the mindset to look at art, the hope rested with the sheer volume of people passing through – 5% of the thousands at Tucson being more prospective buyers than, let’s say, 100% of all visitors to a Tukwila art gallery. The space I had was a large (5000 sq. ft.) grassy area. There was lots of room to display the sculpture (most on pedestals) and for people to walk around. It faced south, the sunlight good all day. For me, pale from the Northwest, it was an almost blissful setting: sunshine, swimming pool, palm trees, and mockingbirds exuberant in song.

I had both fine art and “functional art”. The larger fine art pieces were by: Brian Berman, Michael Binkley, Joseph Conrad, JoAnne Duby, Richard Hestekind, and Michael Jacobsen. I also had a dozen or so smaller pieces contributed by the above and Jim Ballard, Arliss Newcomb, Nicky Oberholtzer, and Carol Way. Smaller still were birds (Binkley), hearts (Way), and “touchstones” (McWilliams). The “functional art” was in the form of both bowls and tables. The tables were sawn and polished slabs of Aphrodite marble (God’s art) mounted on blacksmith-made, wrought iron stands. Two tables were special. Both were done by Michael Jacobsen; one was in the shape of a nautilus, the other was the large bowl/table done at the 1998 Camp Brotherhood symposium.

Wanting to cover all the bases, I also had lapidary items made of Alaskan stone: knives with stone handles, stone spheres, stone eggs. I used small identifying signs as an aid to selling these smaller items; it seems that many people need to be told what they are seeing, even when it is obvious.

And people appreciate smaller-print information, little cues to intelligent choices. I wanted to help: “BIRDS” – “just flown in from Alaska,” “STONE EGGS” – “laid by very cold Alaskan chickens,” etc. There had recently occurred a notorious fossil fake. About three issues ago, National Geographic featured a story about a fossil bird from China that “proved” the direct lineage of birds from dinosaurs. The fossil later was found to have been a composite, a modern day Piltdown man. But fossil birds were on every one’s mind. I had several Binkley birds carved from fossil coral. They had to have a separate sign: “Genuine – from Alaska – FOSSIL BIRDS.” A few paleontologists appreciated the word play.

What sold? A little bit of everything. Hard to generalize. Paul Hawkins was surely right about “functional art.” I sold (or traded) most of the Aphrodite tables, including the two grand ones done by Jacobsen. Several bowls sold, so Ralph has some new places to hide his 30-30 shells. I am happy to report that two large fine art pieces sold. Six smaller sculptures sold. About 20 Binkley birds took wing. Some of the New Age folks found cosmic qualities in the Aphrodite marble and bought hearts and “touchstones.” On final assessment, I think my location at the Ramada was good in general – certainly pleasant – but not specifically good for the sale of upper-end fine art pieces. Next year, I have an opportunity to show art in a much more upscale location. All sculptors are invited to suggest pieces for consideration. I believe Tucson has tremendous potential as a selling venue for both fine and functional art.

We need some kind of descriptive text here.