Home » Journal Articles » Thoughts & Opinions » The Lost Trade of Stone Cutting

By Joe Conrad

Joe Conrad was a valued member of NWSSA for many years and we are glad he shared some of his hands-on, expert knowledge about cutting stone. Since he lived in Portland, Joe usually attended the Silver Falls symposiums, though he did make an appearance at Camp-B.

Have you ever thought about how those old stone churches, so much a part of Portland’s identity, were built? Back in l965, I did some walking with my father through old stone quarries. On those walks he gave me a feel for what it must have been like in his day.

Dad told me that the Knowles, California granite quarry employed 2000 stone workers in l920 when he worked there. They were building San Francisco’s city, state and federal buildings, post offices, courthouses, City Hall and the Customs house. To me, these buildings are the most beautiful parts of San Francisco, all of which were built out of Sierra Nevada granite. The Knowles quarry is still operational, but we also walked around several abandoned quarries. In the lonely foothills of Madera County California, we saw a few granite foundations of stone bunk houses. They’re all gone now, with nothing left but wild flowers, live oak, and abandoned quarry holes full of water. Many old quarries are on private property, with no easy access. They exist all over the country, a remnant of another time.

Here is a list of some cities with urban identities and the stone, from which those identities were built:

Portland Oregon Basalt and sandstone churches

Vancouver, B.C. Granite waterfront and public buildings

San Francisco Sierra Nevada white granite public buildings

New York City Brownstones

Austin Texas Pink granite capital, historic public buildings

Moriello, Mexico Pink limestone

Jerusalem Yellow limestone

Minneapolis Canadian shield granite and Kasota stone

In l917, Portland had a significant stone cutting industry, with seventeen to twenty companies that supported hundreds of people. Times and technology changed over the years and by l980 Portland had only one stone company, which probably supported ten to fifteen people. Of course styles and tastes continue to change, and today, Portland may have around thirty stone companies supporting perhaps 500 people. And even though much has been lost of the old ways, people who work with stone today continue to leave permanent marks on the urban landscape. A landscape that can still be defined by dimensional stone, though each stone’s footprint is actually set by technologies at stone saw mills far from the local stone workers. But let’s get back to the stonecutter, and his long forgotten trade.

As my father and I continued walking around abandoned quarries he told me stonecutters of his era were paid a dollar per hour and train fare to and from their home state. Great wages. By comparison, electricians received 60 cents an hour. No wonder the stone cutters strutted the streets of San Francisco on their Sundays off with their wooden fold-up tape measures sticking out of their back pockets.

But it wasn’t all swagger. Stonecutters in those days worked at both the quarry and the actual jobsite, and I once heard a story about a job shack in San Francisco making so much dust that the insurance rates went up in the business across the street. Because safety practices were almost nonexistent in that era, stone cutters often died early. My father told me he never expected to see 40 years. His three stonecutter brothers didn’t live beyond 45.

As for my stone working history, I briefly apprenticed in a fabrication facility cutting dies, slants, hickeys and bases for monumental dealers. They mostly used 6 inch and eight inch sawn or polished slabs of granite. Stonecutters all pitch differently. These Memorial cutters are offended by point marks or ill-defined corner lines, signs of failure in stone cutting.

The first job I had in this industry was in l959. I was laying out large complex shapes full size on the floor of a pattern room, then making zinc templates of each piece for stonecutters to apply to individual stone while shaping it. I don’t know if those early stonecutters had the luxury of such pattern making, but developing complex stone shapes in three planes was part of their job. My father and my two older brothers could calculate what dad called ramp and twist. I couldn’t, nor could my younger brother who was an artist in stone. The modern era of the stonecutters in the United States was from 1800 to l920, when most were replaced by the gang saw. I read once there maybe 300 stonecutters left in the United States.

As Dad and I continued our walk through the Knowles County quarry, we came across a piece of granite-five feet wide, five feet long and six inches thick lying there among the wild flowers. All the edges were rough split top and bottom with broken faces. Interestingly, there was a perimeter of 3 to 4 inches of point marks all around it. I asked Dad what this was. 50 years later I can still hear him saying, “You don’t know? That’s a level seat! The stonecutter prepared this stone for the surface drifter to hammer point the top flat to his marks.” Later it dawned on me, this is the fundamental beginning of every building stone ever cut. The stonecutter from 1900 to present had the advantage of compressed air to help them shape the stone, but it still all begins with a level seat – the stonecutter’s first step.

I have only found four places in the world where traditional stone cutters are still celebrated, by showing their tools in display cases. There may be others. The first is the state historical Center in Helena Montana and, the second is a state building in Vienna Austria. Both honor stone craftsmen. The third is the Stearns County Museum in Minnesota, where I grew up. This building is located next to a granite quarry that is now used as a nature park. It has a sunken man-made exhibition quarry in it showing the tools of the trade. The Vermont Marble Company is the fourth, and it now has a museum that recalls when their company once controlled almost all the marble work in the USA.

If you want to see a “stone town” not that far away, go visit Lewistown, Montana. Croatian immigrant stonecutters, who settled there in the 1800s, built it out of local sandstone. When I first visited, no one seemed to know the source of the stone. After making inquiries I found my daughter-in-law’s great aunt Mary who was ready and willing to help, eventually taking me to the town’s old quarry. There is a strong sense of local pride in Lewistown where the original stone buildings have not been painted over. For an old stonecutter like me, it’s always gratifying to see good, honest stonework.

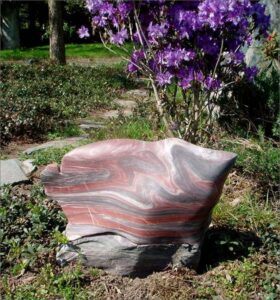

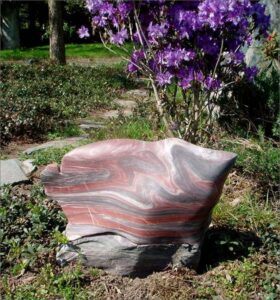

We need some kind of descriptive text here.