Amy Brier is the real thing. She is a working stone sculptor who carves limestone and uses several sculptural media. She is equally comfortable in conceptual art discourse as in restoring a 12th Century French cathedral, and her founding and directing the annual International Limestone Symposium in Indiana (now in its 13th year) exemplifies her belief that the goal of contemporary art is to forge connections between people.

Amy has taught sculpture from South African neighborhoods to NWSSA Symposia; she has exhibited her work from the National Museum of Women in the Arts to Berlin, and she is that rare kind of contemporary sculptor who has actually dissected cadavers in order to understand anatomy.

AB: I grew up in an artistic family in Rhode Island, and knew from early on that I wanted to be an artist. I did my BFA in sculpture at Boston University, and then spent some time carving marble in Italy, where I realized that stone carving was what I wanted to do. At the age of 27 I was introduced to the stone yard of the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York, and I spent 6 years working there, carving architectural ornamentation in limestone. Limestone was the reason that I did my MFA in Bloomington, Indiana, and the reason why I am still there.

I prefer limestone to other stones because of its homogenous quality. It’s soft, and the grain is not an issue; you can go into it from any direction. What might be seen as blandness, compared to other stones, means that form is everything – there is no seduction of color or veining or surface – it is all about the form and the directness of chisel and stone. I use a diamond saw to rough out, but I prefer to use hand tools. There is no polishing or sanding necessary; I finish it with the chisels and that puts life into the surface. I may polish to create contrast, to highlight the chisel finish.

TO: You talk about the humility of limestone.

AB: It is sedimentary and close to the nature that created it. It has not metamorphized, but has fossils and organic material. Limestone keeps me in respect of nature. It is innate memory of the earth, the most direct connection that I can have to the span of history. It also inspires in me a reverence for the process – knowing that this rock has come to me through a lot of effort by other people – and respect for its tradition, being the prominent architectural stone in our nation. I work with Indiana limestone primarily because it is the only American limestone that has both carvability and durability for outside sculptures.

TO: You have developed a series of carved balls to be rolled in a bed of sand – you call them Roliqueries.

AB: Technically they are shaped into balls on a lathe, and then carved in the negative in order to give a positive sculptural impression when rolled in sand. The motifs of many are forms from nature, like snowflakes and oak leaves, fish and spiders – other balls have text. One of them has fragments from the love letters that my parents wrote each other when my father was in World War II.

The carved stone becomes a tool in the creation of an image, rather than being simply a singular art object, and the fixed and permanent stone is juxtaposed with the fluid and fugitive sand image. Viewers complete the creative process as they roll the Roliquery. Art is then momentary and interactive, and I play around with the traditional concept that art is timeless, since even the stone wears down eventually by being rolled in the sand. In this way, my work combines traditional carving techniques with contemporary art ideas such as public interaction and appropriation.

TO: Where do your sculptures come from?

AB: This concept of Roliqueries started in grad school, when I was looking at Mycenaean cylinder seals and conical sculptural forms. I like to make things, but in grad school you can’t just make things because it feels cool. I start with a concept and look for ways to express that concept so that it’s interesting, and also challenging for me.

TO: Do you ever just stand in front of a block of stone and let your chisel do the work?

AB: No, but there are times when I am working on a piece and feel stuck in my brain, and then leave it to my hands to do the work.

TO: For 13 years you have been the director of Indiana Limestone Symposium.

AB: In the European model for symposia sculptors are invited to come together to carve, they are reimbursed, and the works that they produce are left behind. In America we have the workshop model that we know from say, Camp Brotherhood. I wondered why there was no symposium in Indiana with all this stone everywhere, and so I co-founded it 13 years ago and have directed it since. People come from all over the world and from all over this country, with a core group of people that have been coming for years and years. It has become a respected feature of the community as well. For the locals, there really is no other place where people can come and experience the limestone that their grandfathers may have milled.

This September we will have a symposium using the European model for the first time, with a French carver and myself, and the pieces will remain in the community.

Last summer I went to Austria to Krastal, an international symposium that goes 40 years back. We carved a very hard marble together. It was quite a challenge, a very intense communal experience of invited carvers from all over the world who run symposia in their own countries, and then a 3-day conference where each person presented her/his symposium. I was the only American, and the only one who had this workshop model. I had more women participants in mine than anyone else, and more of a free feeling and exchange – not just a bunch of professional artists coming together, but people who come to learn and share and be generous and open with each other.

TO: What do you look forward to, Amy?

AB: I would like to do other things as well. I love teaching. I would love to have a community studio in Bloomington, with workshops and a gallery, where the tourists can come and experience the stone alongside the full Indiana history of cut stone.

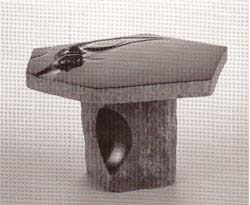

We need some kind of descriptive text here.