Home » Journal Articles » Thoughts & Opinions » NWSSA Women in Public Art

Constance Jones… My Story

I’ve always loved rocks: their color, their strength, their basic-ness, their everywhere-ness. This love started early on, growing up on acreage with massive basalt boulders behind the house. They raised me. I climbed them, lolled away on them in the summer sun, pondered the deep questions of youth from their height, found solace with them in hard times, etched on and chipped on their surfaces and hid among them when it was time to do the chores.

Many years later, when traveling with a group to China to adopt a child, I met a woman in the group named Kalia Gentiluomo who carved stone. I had an undergrad degree in anthropology and archeology and had learned a fair bit about the various stone ages and how dependent humans have been on stone to make tools, create shelter, and express ritual and meaning. I even had done a little flint knapping myself. However, I hadn’t met anyone who carved stone, nor had the possibility that I might be able to carve stone occurred to me.

I was fascinated.

During the trip, I had further conversations with Kalia about stone carving. I was amazed to learn that stone carving was a thing many people were doing. Kalia was a member of NWSSA, and at that time, was a stone carving instructor at Pratt in Seattle. When we got back, I signed up for her next class.

That was my beginning. Since that time, I’ve attended more classes at Pratt as well as most of the NWSSA symposiums, where I learned more of the ways of tools and stone.

The symposiums introduced me to the fortunate (or unfortunate) thrill of collecting stone. I tend to select rock that has some rhythm or movement going on in the pattern it holds. I like to see the rawness of the stone.

When I carve, I like to keep that rawness alive and not transform the entire stone into something made shiny and gemlike. I want there to be enough raw stone so that the stone and I remember its natural face.

I primarily carve parts and shapes of women’s bodies. Stone perfectly exemplifies the historic strength and bodily landscape of women. Some of the elements that make up stone also exist in our bodies.

We have a molecular relationship.

I am interested in the way stone can carry the lines, movement, and form of the body’s gestures. I am interested in the way meaning and expression can be presented in stone. And at the other end of the telescope, I am interested in taking part in the ageless human tradition and process of stonework.

MJ Anderson, 2010

Commissioned through Oregon’s Percent for Art in Public Places Program, “To Scale the Scales of Justice” references figurative classics of art history while presenting the artist’s contemporary interpretation of the symbols of protection and balance practiced within the walls of this justice building.

The sculptures are an allegorical work, a contemporary interpretation of the symbol of justice. Approaching the entrance, the sculptures are classically and symmetrically framed in line with the two side arches of the architectural façade.

Facing one another, the two figures (carved Bardiglio marble) represent the dialogue that takes place in the search for justice, whether between friend and foe, defense and prosecution, or between colleagues.

In the original call for art, the committee was looking for work that would portray justice as protecting a community. Who better to represent the idea of protection than the force behind the will of two mature female figures?

They are mounted on black granite bases with carved steps that represent the steps taken to secure justice. (The Latin root for the words ”to carve” and “stairs” are the same.)

The two figures themselves, allegorically, become the two scales of Justice, creating a dialogue of integrity, fidelity, honesty, and impartiality in weighing truth and equity for the people of Oregon.

Arliss Newcomb

I have a love of beautiful stone. One of my favorites is red travertine. The design had been in my head for a long time, but it took me a while to decide that travertine was what I wanted to sculpt it in. One winter, while working with Joanne Duby at her studio in Art City in Ventura, CA, I found just the right piece. I started roughing out the design there and finished it at my home studio that spring. “Red Flame” was just finished when Wenatchee, WA put out a call for public art, and I submitted the sculpture. It’s on display in front of the city’s convention center. A year later, the city purchased it for their permanent collection.

Verena Schwippert

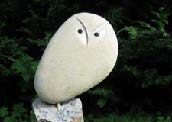

I have completed four public commissions. This one was chosen by the Washington State Arts Commission for Walla Walla Community College. It was installed in 2010 next to the buildings for Nursing and Theater Art. The material is granite, shaped from natural boulders each about 6 tons in weight. Each boulder winds up being about 36″ high, 72″ long on average. Tracy Powell was the very valuable assistant on this project. The title of the piece translates to “By The Hand Of Man”

Ruth Mueseler

“A Child Has Died”, a 14-ton installation of buff-colored granite from the Selkirk Mountains. Selkirk in old Norse means “cathedral of the soul”. The Mother’s Walk group wished to create a memorial space where they could sit and grieve in the cemetery. They had seen my work, and felt the intensity of emotion in it. I began to carve a full size woman curled in grief. Then I envisioned companion stones as benches and was led by circumstance to Beaver Lake Quarry in Skagit County where I found an extremely dense slab of metamorphized volcanic mud with a top coating of white calcite. I carved five pie-shaped pieces which fit together in a semi-circle, their green colors shining through. It took me three years carving the benches at the quarry and the figure at home. The Parks Dept. donated the site and Hoist and Haul brought them to Bellingham.

We need some kind of descriptive text here.