LT: Please tell our readers a bit about yourself.

KH: I was born in San Diego to parents who had recently completed architecture degrees at UC Berkeley. I developed by my mid-teens into an avid rockhound, olla hunter, and rock climber. Successful in school, I eventually earned a Ph.D. in the history of science from Berkeley. Along the way, Sally Brannon and I got married and had three children, and I secured a job at UC Irvine. I taught there for more than three decades. Upon my retirement in 1999, we moved to Seattle so we could be near our elder daughter’s family. I have affiliated here with U of Washington, joined a rockhounding club, and gone into stone sculpting.

LT: Why ever did you take up stone sculpting? I doubt that many historians have become sculptors

KH: That’s probably so. Indeed, when I attended my first stone-carving workshop in November 2000, I was daunted by my complete ignorance of the tools I would be using. I was also worried that I had done almost no free-hand sketching or clay modeling. I began then primarily because Sally, who knew me well from our four decades together, insisted that I give this millennial gift to myself. She was right to do so.

During our European honeymoon, I had excitedly shown her the Louvre’s Egyptian granite sculptures and shared her wonder in Florence at Michelangelo’s “prisoners.” In the ensuing years, she often saw me admiring stone sculptures in galleries and gardens, heard me enthusing about rugged landforms, and chortled when I hauled rocks home that I thought might be fun to sculpt someday. She also noted my enjoyment when, occasionally, I carved and polished pendants from abalone shells and free forms from manzanita branches.

LT: Once started, how have you drawn on your earlier life experiences in your sculpting?

KH: My desire to collect most of the stones that I sculpt originated with my early rockhounding. My preference for harder stones derived from their prominence in the terrains of my youth and their endurance in the many cemeteries that I visited when tracing my family’s genealogy. And my energy and patience came from my father’s example.

LT: Yes, but stone sculpting is more than one’s media and work habits. How did your background influence your tastes?

KH: You’re right, of course. I suppose that I dodged this issue because understanding the origin of one’s tastes is so difficult. My aesthetic sensibilities must have been molded partly by my parents’ architectural ideas, interior decorations, and paintings, partly by my increasingly close attention to geological formations and oceanic, alpine, and desert life forms, and partly by my many happy hours wandering through art galleries. However, I cannot discern precisely how these various experiences lead me now to react to some sculptures with boredom, to others with annoyance that their promise has been incompletely realized, and to a few with unalloyed pleasure.

LT: How would you characterize your body of sculptural work over the last six years?

KH: Another difficult question. Let me just say that I’ve completed over 150 pieces. They’ve ranged in mass from 1 up to 700 pounds and in greatest dimension from 6 up to 66 inches. I started the large majority of my pieces, not with any representational intent, but rather with the goal of dramatizing the charms of the stones utilized. About half of these have been simple basins and about half, more ambitious forms. As will happen during the long hours that go into creating a sculpture, I’ve come to see some of these works (e.g., “Humpty,” “Wild Sun,” “Snake Dance,” “Elbow, Desert Sands,” “Canyon,” and “Devoted”) as highly stylized representational pieces. Of the dozen or so representative pieces inspired by Sabah Al-Dhaher’s teaching, I especially like “Olympia,” “Time Capsule,” “Child’s Haven,” and “Point of Turning.”

LT: Where do you get your stones and how do you select which to acquire from the many available? And how do the stones you use influence the kinds of sculptures you make.

KH: Most of the stones that I sculpt are ones that I’ve found myself along ocean shores, river bars and banks, and desert washes and hillsides. The much smaller number that I’ve purchased come from stone yards/dealers and auctions. And a few have come as gifts from friends and acquaintances. When choosing what to collect for my sculpting hoard, I lean toward sound stones with appealing shapes, unmarred skins, contrasting interiors, and medium to great hardness. It is essential, to be sure, that they can either be moved by hand from their outdoor settings to my vehicle or, if larger, from their dealers’ venues to the studio that I share with Ken Barnes.

LT: Whoa! Don’t you ever start off your search with a design in mind and seek out a stone of the size needed to realize it? And what do you mean by “appealing shapes”?

KH: Yes, I do occasionally begin a stone search with a specific design in mind. Indeed, I’m now carving a commissioned figurative piece from a block of Indiana limestone bought from Brian Berman specifically for this purpose. Much more frequently, however, I choose stones that are similar in shape to ones from which I’ve earlier created satisfying forms. I’ve come to regard such shapes as “appealing.” From time to time, however, I come across a stone that “appeals” even more strongly to me, one that immediately sets me to thinking of designs I haven’t tried before. My goal then is to come up with the shape that best amplifies the beauty of the form already created by natural processes.

LT: Is that the only way your stones influence the sculptures that you create?

KH: No. I also find, as you can well imagine, that a stone’s rind, internal patterning, hardness, toughness, and integrity also play roles in determining the form that I ultimately develop.

LT: Moving on, how have your tools and techniques influenced your sculpting?

KH: Profoundly! You’ll recall that I knew virtually nothing about stone tools when I started out. I have gradually overcome this handicap through my contacts with NWSSA members and at NWSSA workshops. As my versatility has grown and my familiarity with the accomplishments of fellow sculptors deepened, I’ve begun to think that almost any imaginable shape can be created. So, when considering alternative forms, I notice myself creating more ambitious pieces as my toolkit improves. Textures are a different matter. When considering possible textures for a piece on my sculpting table, I often conclude that there is no way to surpass the interest, and beauty, of the eroded and often chemically transformed natural rinds of the stone that I’m carving. If this happens, I’ll settle on a design that incorporates parts of the stone’s original skin.

LT: Let’s get our feet on the ground. Tell us the stories of two recent pieces that you enjoyed creating.

KH: Good idea. The first is “No Better Shield,” which I finished last spring. I collected this granite “feather,” a spall from some nearby boulder, when driving across the Sierra Nevada in 2002. It rested in our studio yard for the next three years because I had no easy way to make any but a circular opening between its two main faces. Then, while at the Camp Brotherhood Symposium in 2005, I saw diamond chainsaws in action, bought a small one from Tom Monaghan, and learned about stone inlaying from Candyce Garrett. Six weeks later, these toolkit additions led me to take the spall to the Silver Falls Symposium as my chief project. There, after establishing its base plane and trimming its perimeter, I chain sawed openings in the stone with help from Candyce and Laura Alpert, polished these openings and the band running through them from the stone’s top to bottom, and created inlay channels with guidance from Candyce. Over the next eight months, I completed the inlaying and based the piece on a three-tiered plinth consisting of diorite blocks that had been pressure-split from two “academy black” risers by Travis Brown’s crew at Marenakos Rock Center. In naming the piece, I was mindful of the fact that, despite the intentions of their makers, all shields leave openings through which determined enemies can attack.

LT: Seems to me that you’re trying with that name to make a political point.

KH: To be sure! But soon after completing the piece, I must admit that I was disappointed to realize that “No Better Shield” also had an unanticipated vulnerability. I had not anchored it securely enough to prevent two strong persons from lifting it out of the base and carrying it away. Once I realized this, I declined an opportunity to show it at an outdoor exhibit that had experienced such hooliganism last year.

LT: Mmm. Perhaps you should have taken your chances. Anyway, tell us the second piece’s story.

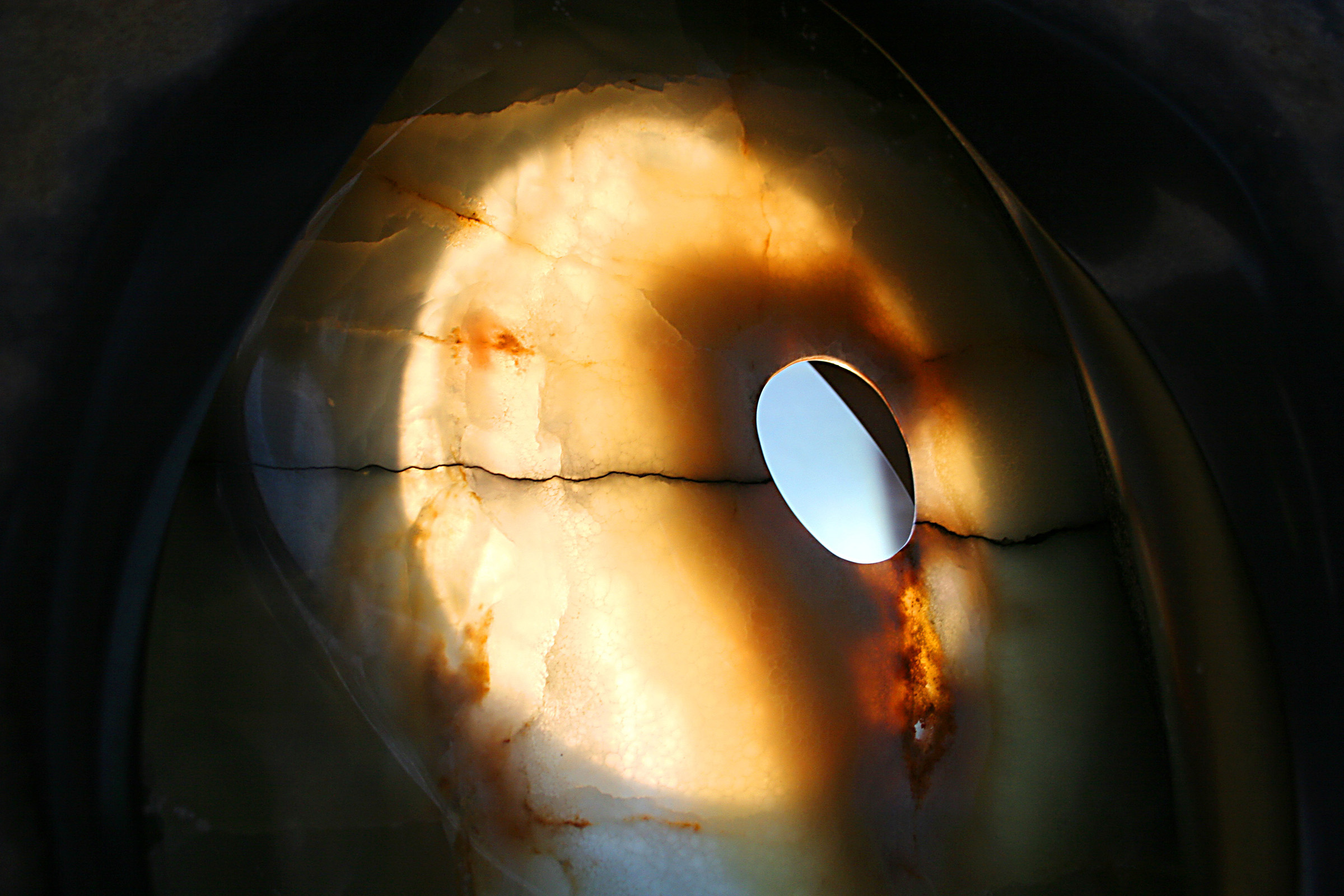

KH: I collected the rhyolitic wonderstone that went into this piece last May from a site that rockhounding friends told me about in Nevada’s Lahonton Mountains. Shortly after getting the stone back to Seattle, I cut off a bruised edge with Ken’s 20-inch chop saw in order both to view its interior (spectacular) and to ascertain its hardness (about 6.5 on the Mohs scale). Then, unsure how I wanted to proceed, I set it aside. When I returned to the stone between the Camp Brotherhood and Silver Falls Symposia, I found myself drawn particularly to a distinct, elegantly-weathered dragon likeness on what had been its skyward surface for the last two or three centuries. I used the chop saw, smaller blades, and a cylindrical grinder to remove the uninteresting areas from the sides of the “dragon.” Then, after establishing my base-plane, I delineated a “spine” on what had been the downward-facing surface and shaped toward this line from both sides by fretting, grinding, and polishing. I also roughed out a base from basanite, a fine-grained, jet-black igneous stone with a wonderful rind that I had found in 2005 near Oregon’s Stinking Water Pass. Shortly after Silver Falls, I set the “Lahontan Dragon” on her base. What I particularly like about this sculpture are the two views it offers of the “dragon” and the ways in which the finished areas and remaining weathered surfaces all complement one another.

LT: Well, that about does it for now, Karl. Thanks for sharing with us.

KH: And thanks to you and others on Sculpture Northwest’s staff for inviting me to be an interviewee.

Website: www.karlsstoneart.net/

Note: Karl Hufbauer passed away January 28, 2020

We need some kind of descriptive text here.